The Application Trap: When “Good Enough” Ensures That You Won’t Be

I was recently approached by a frustrated student who had been actively applying for full-time roles. . .

Yet they had received very few interview opportunities and zero offers. “These companies just don’t see my value – I’m getting an advanced degree and have great prior work experience. They would be lucky to have me,” I was told.

The resulting conversation revealed that they had been very active in applying for roles (dozens per week) – taking advantage of online application portals, AI crafted resumes and dedicating a little time to company and industry research and interview practice. Their efforts were “good enough”. The ability to apply to so many roles was a key advantage, they said.

While conversations like this can be common, they are no means universal among students or job seekers, in general. But self-serving bias can manifest itself in job search struggles with attribution of setbacks to external factors and successes to internal/personal actions. How might one adjust their perspective and move forward with purpose? Ready to look closer?

The Efficiency Illusion and The Compound Effect of Minimal Effort

No question that current job seekers and career explorers are fortunate to have many tools to make the process more efficient – online job boards, interview practice resources and AI. . .for everything. But the reliance on and/or outsourcing such critical components of one’s candidacy can come at a cost. Some hiring managers view the use of AI negatively for the creation of resumes and cover letters. And the debate about that dreaded cover letter – whether anyone reads it, never mind whether it is a factor in hiring decisions – continues. Why bother with one at all? When engaged in a job search, we can succumb to the illusion of efficiency – the idea that the more applications we can process will necessarily lead to more positive responses. We can fail to recognize the hidden cost, however – that by spending less time focused on specific opportunities and on ways we can truly differentiate our candidacy, we risk being generic and unmemorable. In a highly competitive market (or in any market, really), quantity of applications does not necessarily translate to more numerous positive outcomes. In fact, there is a real risk that one is spread too thinly – but believing that efforts are “good enough” which, ironically, almost ensures that they won’t be. And then there is a compounding effect of these efforts – diluted focus results in disappointing outcomes (no responses, interview invitations or offers) which makes this loop reinforcing (candidates redouble efforts to increase the number of applications, assuming external factors are to blame). These experiences can invite a self-serving bias -asking “why don’t employers recognize my value” rather than asking “what can I do to better demonstrate my value to an employer”.

From External to Internal: Shift in Perspective

One way to approach the job search differently is to cultivate an internal “locus of control” – a belief that our own efforts and choices can play a role in success or failure – rather than an external one - a belief that luck or outside circumstances are solely responsible. It is true that external factors can influence outcomes (a difficult job market, the number of applications for a position, etc.) but our own action (or inaction) is important. In these situations, it is helpful to differentiate between factors within and outside one’s control. The resilient path focuses on the former – understanding that applying maximum effort in an application process (differentiating oneself through marketing collateral, rigorous research on the company and industry and in interview preparation), while not a guarantee of success can increase the likelihood of positive outcomes and create long-term agency in one’s career (and life). In short, the question should be “what can I control” rather than “why is the market unfair”.

None of this is to ignore the experience of challenging job search – multiple applications and processes that result in zero positive outcomes is disappointing and it can be hard to stay positive. That frustration and discouragement is real – and it’s ok to take time to sit with those emotions. Even if operating out of an internal locus of control, often the outcomes can be the same for a period of time.

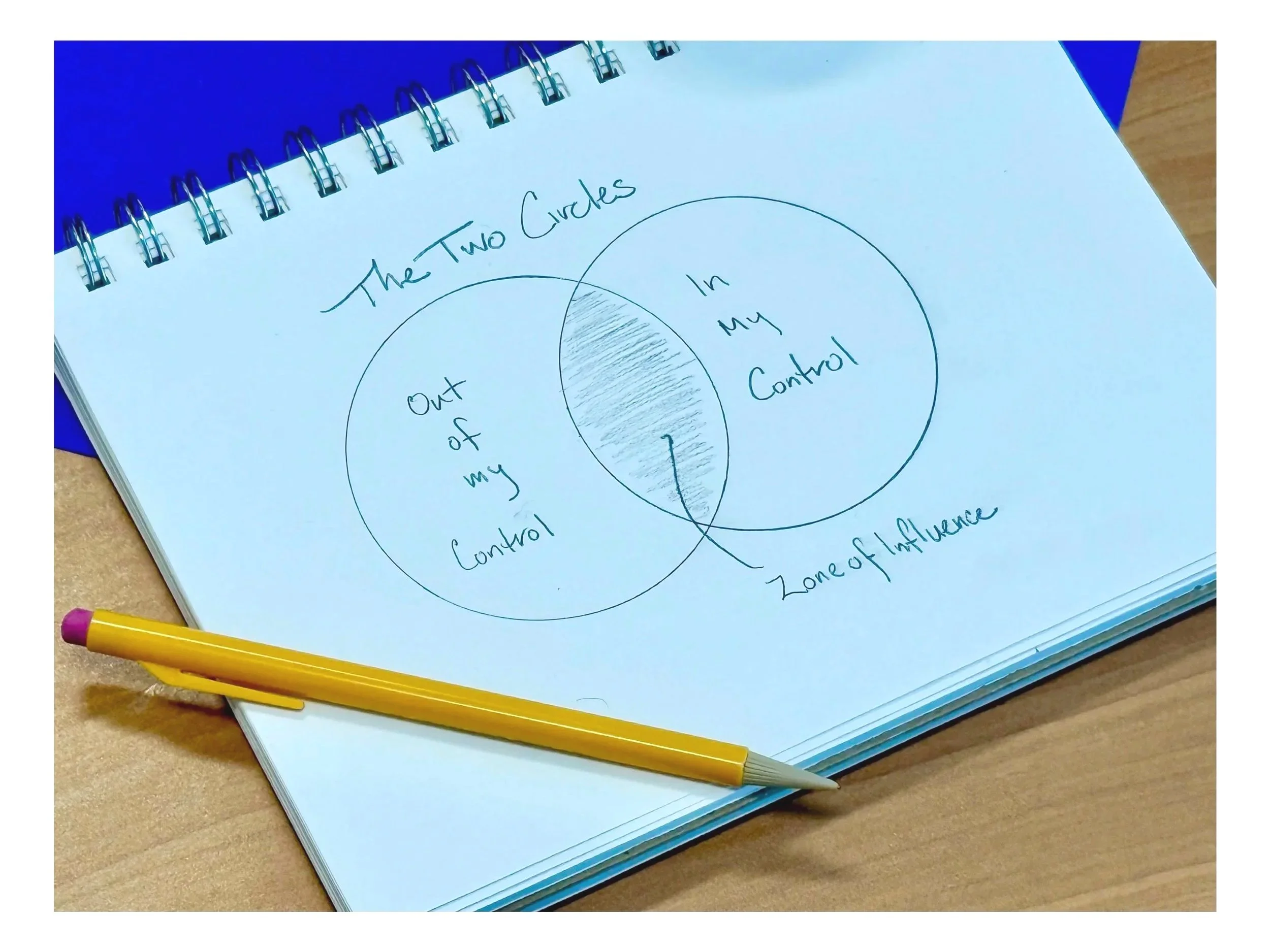

The Two Circle Exercise

One way to break the cycle is to reflect on a recent experience – regardless of its outcome. Take a moment to reflect by imagining a Venn diagram composed of two overlapping circles and write down individual factors for each of the three sections:

Factors Outside of Your Control (Left Circle)

These are the things we must accept – a competitive or difficult job market, the recruiting process, the number of applicants for a particular role – nothing we can do will change these things regardless of their impact on progress.

Factors Within Your Control (Right circle)

These are things you could be doing. It’s all up to you – industry and company research, resume/cover letter editing/tailoring, interview preparation, etc. – with an intensity of focus. Here quality, not quantity, of output is the key measure!

Zone of Influence (Overlap)

You can act on these, but the outcome is not guaranteed. For example, you can reach out to people as part of a networking strategy (within your control), but cannot control how others respond, or if they respond at all (outside of your control).

Now. . make lists under each of these three areas of the diagram – how much time are you spending in each area? Ruminating on whether the market values your skills and experience? That’s outside of your control – perhaps time is better served by crafting a resume and a corresponding story that best articulates your value to the market. Return to this exercise after every outcome – whether the outcome was positive or negative. Reflect on how you might take control in every area where you can!

Final Thoughts

While it won’t guarantee success in every process, this exercise will reinforce the fact that a candidate has control of (and responsibility for) of some of the outcome. Further, they can break free of the “the market doesn’t recognize my value” or “what’s wrong with me” cycle. Ultimately, an approach founded in resilience and proactivity is a far better way to increase the potential for outcomes we desire and to help maintain a positive attitude to move forward.